An Essay for Galerie Taisei’s On-line Virtual Gallery Exhibition on WEB

‘Le Corbusier’s Tapisseries (Tapestries)’

by Misa Hayashi

March 7, 2021

In 1936, Marie Cuttoli asked Le Corbusier to design and draw sketches for tapisseries (tapestries). This was the beginning of Le Corbusier’s relationship with tapisseries (tapestries).

Since ancient times, large tapisseries (tapestries) that adorned and decorated the walls of châteaux (castles), aristocrats’ residences and churches were not only appreciated for their beauty but also considered useful because the heat retaining property of woven fabric eased the effect from severe cold climate of winter. Nevertheless, with the changing times, demand for the high-grade woven fabrics such as the Gobelins tapisseries (tapestries) dropped sharply and became obsolete and fell into a precarious state. In the course of great social change that occurred in the nineteenth century, with the advancement of the masses, the main reason was the fact that the number of large mansions and residences that decorated tapisseries (tapestries) decreased. Moreover, another factor was that in the outbreak of plague, it was found that tapisseries (tapestries) provided an ideal place for mice. Consequently, tapisseries (tapestries) were removed from the walls and incinerated, and thus, were shied away from being hung again. And instead, the wallpapers gained the popularity.

It was Marie Cuttoli (1879-1973) who worked on the movement to revive the declining French tapisseries (tapestries). Marie was an Algerian-born woman who had been involved in activities such as holding workshops for traditional carpets locally. Subsequently, she married Paul Cuttoli who was a French diplomat serving as the French governor of Algeria. Then, Marie Cuttoli opened her workshop and gallery in Paris, and interacted with artists and designers. Afterward, she commenced the movement for revitalizing the French tapisseries (tapestries). She was also known as a collector of art works.

Madame Cottoli made good use of her artistic contacts and set forward to gain permissions from such artists as Georges Braque and Fernand Léger, et al., to divert and use the designs of their already drawn oil paintings for her production of tapisseries (tapestries). Then, she followed and commissioned original designs/sketches for creating her tapisseries (tapestries) based upon those designs/sketches. These works of her tapisseries (tapestries) were well received and attracted attention.

Although, Le Corbusier had no prior opportunity to work on the production of tapisseries (tapestries) up until then, he must have been quite interested in the fact that Fernand Léger and other artists of whom he knew were involved in the production of Madame Cottoli’s tapisseries (tapestries), so accordingly, Le Corbusier must have been, no doubt, very pleased with the request from her. Later on, when the Editions Tériade in Paris published a series of print collections by celebrated painters, and his works were also added to the lineup, Le Corbusier was overjoyed. Likewise, he must have been just as happy in his involvement in the creation of her tapisseries (tapestries) as that time. While inasmuch as being an architect, because Le Corbusier put effort into his activities as a painter much more so than others imagined, and accordingly, he possessed a persisting wish to be recognized as a painter.

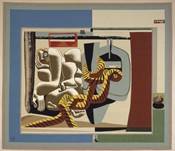

In this way, Le Corbusier designed and painted a work for her tapisserie (tapestry) entitled ‘Marie Cottoli,’ with his requester’s name as its title. This work was painted in 1936 and the tapisserie (tapestry) was completed in the following 1937. The work depicted a woman lying down relaxing by a small boat and a mooring line, a motif of which Le Corbusier preferred in his painting in the 1930s.

The fact this was the only work he collaborated with her notwithstanding, in fact, Le Corbusier continued and maintained interacting with Madame Cottoli since then. In later years, Le Corbusier considered tapisserie (tapestry) as an important work of art for architectural space, and thus, began producing actively. However, at that time, he most probably did not yet have an idea how to utilize a tapisserie (tapestry) in his architecture.

In the mid-1930s when Le Corbusier produced his tapisserie (tapestry) ‘Marie Cottoli,’ it was generally considered that tapisseries (tapestries) belonged to a kind of high or lofty works of art only to be seen and appreciated by visiting the aristocratic mansions and residences. However, there began a widespread movement in France to popularize tapisseries (tapestries) as a familiar form of art that everyone could see anywhere. With the establishment of the ‘Artistic Association of WALL ART’ (‘l'association artistique de l'ART MURAL’), with which Le Corbusier had joined and participated, in the ‘1937 Paris International Exposition,’ there were numerous exhibits of large murals and photomontages that were produced large in size and as easy-to-understand works of art.

Pablo Picasso created ‘Guernica’ for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Expo which, as well known, measured at a height of 3.5 meters and a width of 7.8 meters. Likewise, Raoul Dufy produced for the ‘Electricity Pavilion’ (‘Pavillon de l'Électricité’), an immensely large fresco work ‘Electricity Fairy’ (‘La Fée Electricité’), with a height of 10 meters and a width of astounding 60 meters. Additionally, the enormous works such as Robert Delaunay’s ‘Rhythm’ (‘Rythme’) and Fernand Léger’s ‘Transport of Forces’ (‘Le Transport des Forces’) were produced to adorn the walls of various pavilions. Le Corbusier also filled the walls with large photo-collages and painting panels in his own the ‘Temp Nouveaux Pavilion’ (‘Pavillon des Temps Nouveaux’).

Even in the twentieth century, when large tapisseries (tapestries) and large mural paintings and frescos were no longer produced for châteaux (castles) and churches, etc., many large works of art were still produced during and after the mid-1930s in the Mural Movement in Mexico, as well as in the US and Europe, and succeeded in attracting the eyes of people.

However, after that period, World War II had ensued, and it became a difficult time for the creation of art works, and as such, the tapisseries (tapestries), which just began to be recognized as a new form of artistic expression, were forced to be suspended again.

There is another artist who should not be forgotten in terms of the revival of tapisseries (tapestries). That artist is Jean Lurçat. Although little known in Japan, he ought to be regarded as a true genius of tapisseries (tapestries). Madame Cottoli was an excellent producer cum patron of the tapisseries (tapestries) but she never produced herself. On the other hand, Jean Lurçat was an artist, and a person who made the art of tapisserie (tapestry) known to the world through his own work.

Jean Lurçat (1892-1966) was one of the representative French tapisserie (tapestry) artists and his younger brother André Lurçat was an architect. Jean Lurçat was from the northeastern France and studied in Nancy and Paris. As he started working as a painter, concurrently, he began producing his first tapisserie (tapestry) in 1917, and in a span of ten years since then, he created ten works of tapisseries (tapestries). He interacted with numerous artists, and became involved in costume designs, stage-set decorations and interior design. In Aubusson, which was famous for the production of tapisseries (tapestries), in 1933, he had created and sewn his tapisserie (tapestry) following his new and robust weaving technique he developed.

He considered a tapisserie (tapestry), as an architectural partner and component, was custom-made for a large wall and permanently in existence in the installed space, rather than being woven textile imitations of paintings. Accordingly, he continued to disseminate the attraction of tapisseries (tapestries) to the world through his own works. His works of tapisseries (tapestries) decorate the walls of such places as churches, and are stored as collection in museums around the world.

His tapisserie (tapestry) ‘Apocalypse’ (1946) at the Ēglise Notre Dame de Toute Grāce du plateau d'Assy (Church of Our Lady Full of Grace on the Plateau d’Assy) that expressed a partial scene of the Apocalypse is indeed a masterpiece. Furthermore, it is also known that a Catholic Father Marie-Alain Couturier, who not only commissioned Le Corbusier to design Chapelle Notre-Dame-du-Haut, Ronchamp (1950-55), also commissioned numerous other artists such as Marc Chagall, Henri Matisse, Georges Rouault and Fernand Léger, et al., to create works that decorated the church.

Many works of Jean Lurçat are featured with constellated images of sun, stars, moon and flowers set in the mainly black and dark navy blue background, having characteristics with each outline depicting a strangely prickly expression, and considered as works that one would not forget once seen.

In 1948, at the suggestion of Pierre Baudoin, who was an art school teacher in Aubusson in central France, Le Corbusier decided to work once again on the production of tapisseries (tapestries). When Pierre Baudoin was appointed to teach in Aubusson, he became passionate about revitalizing the local tapisserie (tapestry) industry. Hence Baudoin approached Le Corbusier to collaborate.

Le Corbusier produced his tapisseries (tapestries) from this time onward until his death in 1965. And accordingly, the catalogue raisonné of Le Corbusier’s tapisseries (tapestries) lists 31 works including the theater stage curtain at the Shibuya Tokyu Bunka Kaikan in Tokyo (which is now preserved after the demolition of the building), however, because there are some works with the second versions, and, as well as a case of over 40 individual tapisseries (tapestries) at Chandigarh High Court that are counted collectively as one work, therefore, by counting each all separately in their entirety, Le Corbusier produced works of tapisseries (tapestries) with more than 40 different designs. Furthermore, there are some of those tapisseries (tapestries) that were woven each as a single piece from a particular design, while including those woven after Le Corbusier’s death, and there are also cases where 9 tapisseries (tapestries) were woven multiply from one design. Consequently, in total, 134 pieces of tapisseries (tapestries) were produced.

(From ‘Le Corbusier Oeuvre Tissé (Woven Work),’ Aubusson, Philippe Sers, 1987)

These tapisseries (tapestries) were designed and drawn by Le Corbusier and produced under the guidance of Pierre Baudoin. Most of the works, excluding those produced in India and Japan, were woven in such workshops as Ateliers Tabard, Ateliers Picaud and Ateliers Pinton located in Aubusson and its surrounding areas.

After WWII, inasmuch as it was the invitation from Pierre Baudoin with which Le Corbusier started producing his tapisseries (tapestries) and hanging them in his architectural work, there were also several other reasons why Le Corbusier continued to work on the production. While one reason was the evident similarities between tapisseries (tapestries) and mural paintings (or frescos), another was to solve the physical problems deriving from exposed concrete construction. With those in mind, Le Corbusier strove to come up with and create his own new concept.

Le Corbusier had been painting murals since the late 1930s. This coincided with the period when he was involved in tapisseries (tapestries), as well as overlapping with the time of establishment of the ‘Artistic Association of WALL ART.’ (‘l'association artistique de l'ART MURAL’).

His first mural was painted on the wall of a wooden country house in Vézelay in central France owned by his friend Jean Badovici, an editor of an architectural magazine. Badovici owned a number of country houses and initially asked his friend Fernand Léger to draw a mural painting on one of them. However, upon hearing this, Le Corbusier begged Badovici to let him also draw the mural. And thusly, Le Corbusier was elated as he successfully received an opportunity to paint on the wall of another of Badovici’s country house, so he enthusiastically worked on the production of the mural.

During the early half of the 1920s, Le Corbusier, disliking wallpapers with giddy floral designs and annoyingly large patterns, insisted that each wall should be painted separately in a single color and finished limpidly. By doing so, wall hung paintings, seemingly buried amongst the patterns of the wallpaper, then, stood out, as well as the profile of furniture in the foreground became clearly visible. Moreover, the walls of rooms were painted differently in a single color each, whereby each room was accorded with, depending on the color of each wall, varying distinctive characteristics such as of providing a sense of brightness and warmth, enhancing a sense of perspective, and bestowing a sense of highlighting light and darkness, as well as rendering a sense of unity with the greenery outside.

In the 1930s, Le Corbusier designed and worked on large steel and glass structures such as a large office complex (in Moscow, USSR), Soviet Union Centrosoyuz Building (1933), and a series of collective housings such as an apartment building in Geneva, Switzerland, Immeuble Clarté (1928-32), and an apartment building in Paris, Immeuble locatif à la porte Molitor (1931-34).

Furthermore, since the latter half of the 1930s, Le Corbusier began to find pleasure in making the entire wall into a painting of his own by drawing murals. Of course, then, it went without saying that not only nothing was placed in front of the wall-mural (for being his art work now), but also the room itself, wherefore, became a space to view and appreciate Le Corbusier’s huge art work. Le Corbusier did not merely draw his paintings but also came up with a technique to create his murals by enlarging photographs, which he considered as his method in recreating or re-producing his own work by utilizing photographs.

For Le Corbusier, starting from undertaking the creation of murals that led to his venture in re-challenging with the production of tapisserie (tapestry) must have been a quite natural process.

Going through the period of war, and then, after WWII, Le Corbusier’s architectural work became known for strongly promoting its exposed rough concrete finish typically referred to as ‘Brutalism architecture.’ Especially, the large public buildings in Chandigarh, India, which Le Corbusier was engaged since 1950, manifested a massive and powerful formative composition.

The site where the largest number of Le Corbusier’s tapisseries (tapestries) were hung was the High Court building (1954) in Chandigarh. The space made of exposed concrete finish had resonating and reverberant acoustic properties. In order to solve this problem, tapisseries (tapestries) were adopted. A total of nine tapisseries (tapestries) were adorned, one for the wall of full bench and eight for the wall of the petty benches. The highly sound-absorbing tapisseries (tapestries) not only compensated for the shortcoming characteristics of exposed concrete finish, but also successfully provided liveliness as well as creating a different atmosphere for each room by applying colorful surfaces on the gray concrete wall surface. These tapisseries (tapestries) were designed by Le Corbusier and produced by a textile factory, East India Carpet Company Ltd., in Amritsar (located due northwest of Chandigarh).

In addition to these tapisseries (tapestries) designated for hanging on specific walls, Le Corbusier also produced many tapisseries (tapestries) that were non-designated and independent. While the tapisseries (tapestries) in each rooms of the High Court building were specifically non-narrative due to the nature of the courtroom, and so these works of tapisseries (tapestries) were designed with geometric patterns and colors to be savored and enjoyed. On the other hand, those works of tapisseries (tapestries) not tailored to any particular location were designed as independent works just like his oil paintings.

Unlike the tapisseries (tapestries) possessing a permanent relationship with the building, it is not really possible to find an affinity or compatibility with the places where these independent works of tapisseries (tapestries) are hung. Rather, by producing actively these independent tapisseries (tapestries), Le Corbusier might have expected or aimed to have the space itself to somehow convert or transform into a certain Corbusian space-notion which was suggested by each of the independent tapisseries (tapestries) accordingly.

The motifs of his tapisserie (tapestry) works overlapped with his oil painting and collage works drawn at the same period, due to the technical feature of textiles, the tapisserie (tapestry) works were characterized by more graphic, simpler and clearer designs and colors. In Le Corbusier’s painting works since the 1950s, characteristically, the lines and color planes were not necessarily always aligned. And in his tapisserie (tapestry) works, that characteristic became further emphasized as the color planes were enlarged with less number of colors, and appeared as if large color papers were placed. There, thick and bold, and thin and fine lines unique to Le Corbusier were well expressed in the woven fabric, tapisseries (tapestries). As a result, a sense of mysterious depth was created there.

The size of many of these tapisseries (tapestries) was based on the Modulor. The Modulor was an original measure Le Corbusier devised by combining the anthropometric scale of proportion and the golden ratio. The year 1948, when Le Corbusier started to collaborate with Pierre Baudoin on the production of tapisseries (tapestries), also coincided with the time when he was working on his research of Modulor. According to his premise, the living space created based on the Modulor, which he advocated to be a suitable scale for people, would naturally provide a comfortable size for people. Therefore, by installing his tapisserie (tapestry) made in the size of the Modulor in a room, presumably, the space would instantly become Le Corbusier’s space granting a good and comfortable feeling. (Although the actual size of his tapisseries (tapestries) had some variations, basically, he considered 2.26 meters to be the set height.)

Le Corbusier asked the purchaser of his tapisserie (tapestry) with a request for how to install it. That was, to be sure to display it standing up from the floor. For Le Corbusier, tapisseries (tapestries) signified as equivalent to mural paintings expressed in woven fabric. As the difference rested merely on the media of expression by painting with paint as opposed to by weaving with fabric in the production method, therefore, it is simply synonymous to taking a mural painting of 2.26 meters high based on the Modulor on a wall, and transforming it into a removable woven fabric.

Thus, just as the wall rises from the floor, the tapisserie (tapestry) must also rise from the floor. In other words, even if Le Corbusier’s tapisserie (tapestry) was in actuality hung from the ceiling, as an image, it stood on the floor. His tapisseries (tapestries) must be recognized as “movable walls” ━ or in his own words, ‘muralnomad’ (nomad-walls). Consequently, wherever his portable and installed tapisserie (tapestry) may be located, it would transform into a space with a wall created by Le Corbusier.

There is a photograph of the study of Jorn Utzon, an architect known for designing the Sydney Opera House (1973). The photograph depicted Le Corbusier’s tapisserie (tapestry) which Utzon possessed as hung on the wall so that it almost touched the floor just as the way Le Corbusier wished. Presently this tapisserie (tapestry) of Le Corbusier which Utzon possessed was acquired by the City of Sydney, Australia and made publicly available for viewing. Additionally, Le Corbusier held several exhibitions of his tapisseries (tapestries), and looking at the photographs of the venues taken at that time, Le Corbusier appeared to be adjusting the position of the height of tapisserie (tapestry) by himself so as to make the bottom of exhibit would be placed very close to the floor. Likewise, seeing the exhibition scene at the ‘Pavillon d'exposition ZHLC (Maison de l'Homme)’ (The Center Le Corbusier) in Zurich, Switzerland, the tapisserie (tapestry) was also installed low in a position almost touching the floor.。

Le Corbusier’s tapisseries (tapestries) were often large in size because he aimed those to be (virtual) walls. Among them, the largest textile work was the theater stage curtain Le Corbusier designed for the Shibuya Tokyu Bunka Kaikan (1956, but presently demolished) in Tokyo. As Junzo Sakakura, a Corbusian apprentice and who designed the building, requested Le Corbusier to design a theater stage curtain for the movie theater ‘Pantheon’ in the building. So it was designed by Le Corbusier and produced by Kawashima Selkon Textile Co., Ltd. in Kyoto, Japan.

This theater stage curtain belonged to as part of a series of Le Corbusier’s works depicting ‘bull’ as a motif. As such, it was titled ‘Taureau XIV (Bull XIV).’ Naturally, since being a theater stage curtain, it had to cover completely from the floor to the ceiling, thusly the work was extra-large in size with a height of 9.8 meters and a width of 23.6 meters. The theater stage curtain was removed when the building was closed in 2003, and hence, the original has been preserved and a replica in reduced size made in its place has been exhibited from time to time at the Shibuya Hikarie, a skyscraper built on the same site. Incidentally, the theater stage curtain produced by Pablo Picasso for the ballet ‘Parade’ (1917), well known as a large size work measuring at a height of 10.5 meters and a width of 16.4 meters, was not made of a woven fabric as it was drawn on canvas with tempera

For Le Corbusier, in the 1920s, the walls of the rooms were considered as merely a background that highlighted and complimented the objects placed in front of the walls, and the walls also acted to change the atmosphere of the rooms according to the color of the walls. However, the walls themselves eventually became transformed into his work of art so as to be appreciated. Le Corbusier’s means and method to sublimate walls into works of his art was the mural paintings with paint, photographic murals and tapisseries (tapestries) with textile of woven fabric as well. The tapisseries (tapestries) for Le Corbusier were not only installed to suite his architecture as an element of his composite art, but also it became indeed portable and movable walls, i.e., ‘muralnomad’ (nomad-walls) which possessed the power to transform the installed space wherever it might be into the space of Le Corbusier.